The Belgian Canary By Donald Skinner-reid

I had been wondering where I might find some more detailed, modern works on the Belgian canary, the Bossu Belge, Belgische Bult or Belgian Bump. Of course, we all know about John Robson’s1903 book but I rather wanted something more up to date to tell me the history from Robson to today.

Step forward – unasked, but as if reading my mind – my friend Bart Dupon of Flanders who pointed me to a blog by my other Belgian friend, Andre van den Eynde.Laziness might encourage me to say “Look at the blog” but I’m aware that not everyone has a

computer or smart phone and even if they do, the article may not easily translate on screen.The particular article is well researched and contained many gems of information which fascinated me and might you too.

The bird appears to have been developed in the Flanders cities of Brugge (Bruges), Ghent and Antwerp in the 16 th century. It is thought to have been bred in monasteries from the Waterslager canary for 150 years before 1780 and became known and the great Ghent bird. The 1906 book by Dr

Karl Russ, “Der Kanarienvogel”, has a description of the bird as being “smooth feathered with an upright back, high shoulders, a long narrow neck and small ornate head”. The names Bossu or Bult were not used. It is clear that three variants of the bird were developed in The Netherlands at around this time. “The Dutchman” was a large frilled bird; “The Belgian” a large bird and essentially similar to the current incarnation and, much to my surprise, “The Brussels” which is generally regarded as the Scotch Fancy. That is an interesting take on the origin of the Scots of which, as Wil Cummings writes

“the past has drawn a veil over the exact means and date”. Perhaps that creation myth of the Scots in Blakston’s “the Girvan pair” has just seen the veil lifted?

The all too frequent crossing of the frilled birds with the Belgian and the Scots lead to deterioration of the Belgian itself. Many Scottish breeders bought Belgians to improve the Scots stock and we have all read how there was a time when the two varieties became almost indistinguishable, with

both “mongrels” exhibited in the same class. By the end of the first World War, as any visitor to Flanders will have seen, not only was the land and

lives of many Flems destroyed but the Belgian stock was almost extinct. Andre writes that very few specimens were left. In the 1920s, two Belgian breeders, named Cambeau and Adrien Dawans of Liege started to reconstruct the breed using the Malinois, Yorkshire and South Dutch. In 1937 they

discovered a stock of purebred older birds with a breeder named Lapaille and by war’s outbreak some progress had been made only to be dashed by the battle we know as that “of the Bulge” in the winter of 1944.

Not defeated, Dawans began again in 1952 to reconstruct the breed. He acquired from the remnants of stocks, birds sufficiently close to the breed and by 1958 was able to exhibit birds we would recognise today as the modern Belgian. 1969 however, saw the loss of 180 birds due to disease.

Dawans almost gave up but his surviving stock of 5 cocks and 3 hens, skillfully bred with old style Yorkshires from a M. Clermont by the breeder Joseph Watrin, saw the breed finally rescued and named the Bossu or Bult in honour of Adrien Dawans.

Andre writes that all modern stock come from these birds. I would recommend a reading of Andre’s blog for more detail.

The Belgian Hump By André Van Den Eynde

The Scots Fancy and the Belgian Bump or Hump/Bossu Belge each carry their nation’s pride as bearers of their country’s name. Other varieties carry their county name but these two take the nation’s. The Belgian also has the credit of being the base of many, if not all, of the “birds of position”

or posture canaries. The Belgian Bump we know today is the result of selective breeding by Mr Dawans with surviving stocks after two world wars which ravaged Belgium. After research and several failures, Mr Dawans managed to develop a canary with the characteristics of the former Belgian Hump. He first exhibited his birds at Verviers on 3 December 1958. There has been a revival of the breed with its popularity growing. It is a relatively large breed (17cm). Its length is not always noticeable because of the posture. In larger breeds frequently the number of chicks per pair may be on the low side. An average 4 to 5 chicks per pair over two rounds may be considered normal. The youngster with the best qualities in a nest is usually the one with the longest neck. This may, in turn, cause the chick to lift this long neck for the least time in his first few days of

life which may result in it lagging behind in its growth. To prevent this, one can do a nest check in the evening and possibly top up the crop so that they get through the night. When looking for breeding stock, remember that you need a robust body shape with sufficient width

in the shoulders. The length of the neck should be one third of the bird and the body and tail the remaining two thirds. Pairing two long-necked birds can come at the expense of width in the shoulders and slimming of the body. The long neck will influence the length and slimness of the bird which can make the shoulders too narrow.

The shorter necked bird will give a more robust body and broad shoulders which give substance to the overall body especially in width. This factor will also have an impact on the head and ensure that it will appear heavy and full and will often be a bit short. The best pairing is this one that matches the two lengths of neck and body shape, combining the two factors in the offspring so producing the best showbird.

The biggest misconception of the Belgian Bump is that it is the enthusiast who is going to teach the bird the right attitude and correct posture.

A good posture is an innate trait. Of supreme importance is the correct positioning of the legs on the perch and their position vis a vis

the bird itself. If the legs are too rigid and stilty, especially if they are positioned too far in front of the bird the result will be that the bird is not completely vertical; sometimes if the legs are too far back the result will be that the tail goes under the perch. The correct posture is where the shoulders, back and tail form one straight vertical line; one can see this at a glance when one takes the bar of the cage as a reference line. The neck is stretched forward and forms an angle of 85° with the back line. In rear view, the head is no longer visible. The training that the breeder can do consists of getting the birds that possess the qualities to adopt their posture at the desired time, i.e. when the bird is before the judge.

How do you do this? Puts some birds together in a breeding cage and place a domed cage [or tunnel cage like the Yorkshire] so that they can go in and out of the show cage. Once they feel safe in the domed cage, one can place them in it for a long time and hang the cage from the ceiling of the

birdroom so that one can walk under the cages. Tapping with a stick or a ballpoint pen or gently scratching the base of the cage with your nails, does the job of getting the bird’s attention. If you do this regularly, the birds will quickly recognize it and be wary and so tighten up and adopt the posture.

When you enter the birdroom for daily feeding etcetera, the birds will now observe everything from the height and in their posture. Then start to alternate the places the bird’s cage is in, in the birdroom. Never let the bird sit for longer periods than 2 to 3 days in its show cage once it is finished.

Letting the bird sit in his show cage too long will make the bird less alert during a show and it will work less hard at adopting the posture.

The standard awards points for posture (40points), body shape (25points), head and neck (12points),which are the main components of a good Belgian Hump. Lesser points are for feathering (8points),size, legs and tail each with 5points. Although lesser in points, these aspects should not be forgotten

in order to create the overall picture as close as possible to the standard.

The shape of the body is triangular both in front, side and rear view. The shoulders should be wide and high. The proportions of the bird are one third neck and two thirds body. Between the shoulders there should be only a slight depression or valley when the bird is in posture. The stiff neck and head

should be in one line without depression between the head and shoulders.When assessing the posture, an angle above 90° is as wrong as one that goes deeper than 80°. In recent years there has been a tendency to award more points to the deeper the posture. Some birds that showed a 45° angle in posture have been rewarded. Even now, pictures on social media often appear of these birds with too extreme an angle tending more to the number 1.

In the future, there may be a proposal to change the standard. The points scale could be adjusted. The points for the tail disappear and are added to those for feather, neck and head. The long-standing reference to the number 7 for the correct posture could also disappear and be replaced by

an angle of between 80° and 85°. I hope that all the canary lovers who want to try the Belgian Hump may have found some inspiration

in this article. There is nothing more beautiful than a perfectly presented Bump when he stands in a working position looking the judge straight in the eye and stands in perfect posture even before the judge has the chance to take out his ballpoint pen. As a lover of the bird, you can then enjoy the

knowledge that this is something you have worked on together and the merit can be divided between the enthusiast and his Belgian Bult.

Giboso Espanol

Standard Description of the Spanish Giboso Canary

Position and Type

In the shape of a figure “1”.

In working/show position the head and the neck form an angle of 45º – 60º with the body.Showing distinctly the areas of frilled and smooth feathering.

Neck

Very long, slender, smooth feathered and projecting downwards.

Legs

Very long and stiff, thighs devoid of feather on the front and angled slightly back.

Jabot

Proportionate, with frilled feathers that curl inwards from both sides towards the centre, in such a manner as to expose the totally bare breast bone.Underparts to be smooth-feathered.

Wings and Back

Long, close fitting to the body, without crossing and with the tips lying off from the body.Proportionate, with high shoulders showing symmetrical frilled feathers that fall to both sides from a central back parting to form a mantle which is sparse and close fitting to theback.

Size

Minimum 17 cm.

Head

Snake-like and proportionate, smooth feathered. Beak conical and proportionate.

Tail

Proportionate, narrow, curving slightly inwards to just touch the perch.

Fins (Flanks)

Frilled feathers that part from both sides of the body to form two symmetrical small fins that curve backwards.

General Condition

Clean and healthy, well used to the cage.

Feather quality: tight and close-fitting over the areas of smooth feathering and sparse overthe areas of frilled feathering.

Colour: All colours are allowed.

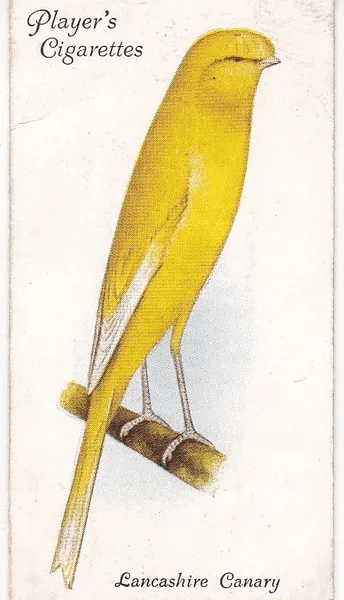

Lancashire Canary

The Lancashire Canary was originally known as the Manchester Coppy or Manchester Fancy – since so many of the breeders lived in that city. This canary is the largest of all English canary breeds, being strong and robust and standing a head taller than any of the others.

The Lancashire Canaries are seven to eight inches long and are heavy in body – and appear as giants when compared with ordinary canaries. This ‘giant of the fancy’ was used to transfer size into other breeds including Crested Norwich, and the Yorkshire.

This canary is a bold and upstanding bird which should never crouch or lean across the perch.

It is a crested variety in which two types of individual are to be found, namely those with a crest (known as “Coppies”) and those without (known as “Plainheads”). Both form an integral part of the breed as a whole.

The Lancashire is always bred in the clear form, either yellow or white, with no variegation such as is found in other breeds of canary, and the only departure from this ideal that is allowed is in the form of a grey or grizzled coppy in the crested birds.

Show Standards:

The following standards were drawn up by the old Lancashire and Lizard Fanciers’ Association and which has been adopted by the Old Varieties Canary Association:

- The LANCASHIRE should be a large bird, of good length and stoutness, and when in the show cage should have a bold look.

- The Coppy (crest) should be of a horse-shoe shape, commenc ing behind the eye line and lay close to the skull, forming a frontal three-quarters of a circle without any break in its shape or formation, and should radiate from its centre with a slight droop.

- There should be no roughness at the back of the skull.

- The neck should be long and thick, the feathers lying soft and close, the shoulders broad, the back long and full, and the chest bold and wide.

- The wings of the Lancashire should be long, giving to the bird what is called a ‘long-sided’ appearance.

- The tail also should be long. when placed in a show

- cage, the bird should stand erect, easy and graceful, being bold in its appearance, and not timid or crouching. It should not be dull or slothful-looking, and should move about with ease and elegance.

- Its legs should be long and in strength match the appearance of the body. when standing upright in the cage, the tail should droop slightly, giving the bird the appearance of having a slight curve from the beak to the end of the tail.

- The Lancashire should neither stand across the perch nor show a hollowback

- .It should have plenty of feather, lying closely to the body, and the feather should be fine and soft.

Lizard Canary

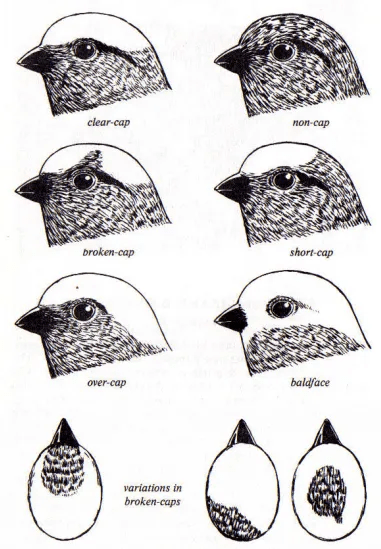

One of the most identifiable features, at first glance, of the Lizard Canary is the cap. The feathers of the cap, in contrast to the body, wings and tail, are clear. The cap should be an elliptical shape starting at the beak, extending over the eye and ending in a smooth curve at the back of the head. A perfect clear cap is rare with many birds showing dark feathers to some degree, and this gives rise to the classification terminology, clear cap, broken cap, non cap etc.

LCA show classification

A Clear Cap Lizard (CC) is one whose cap is perfectly clear of dark feather or feathers and has reasonable regular edges.

A Nearly Clear Cap Lizard (NCC) is one whose cap contains a dark feather or feathers which cover an area of not exceeding 1/10th of the total area of the cap.

A Non Cap Lizard (NC) is one whose head and neck are quite clear of light feathers.

A Near Non Cap Lizard (NNC) is one whose head and neck are marked by a light feather or feathers to an extent not exceeding 1/10th of the normal extent of the Lizard Cap.

A Broken Cap Lizard (BC) is one whose head and neck feathers disqualify it from being classed either as a Clear Cap or Nearly Clear Cap, or as a Non or Nearly Non Cap Lizard.

An Over-capped Lizard is one whose cap extends too far down the back of the neck. This is a serious fault.

A Baldfaced Lizard is one whose cap extends outside the bounds of the cap below the eye or below the upper mandible.This is a serious fault and the bird should not be used in a breeding programme.