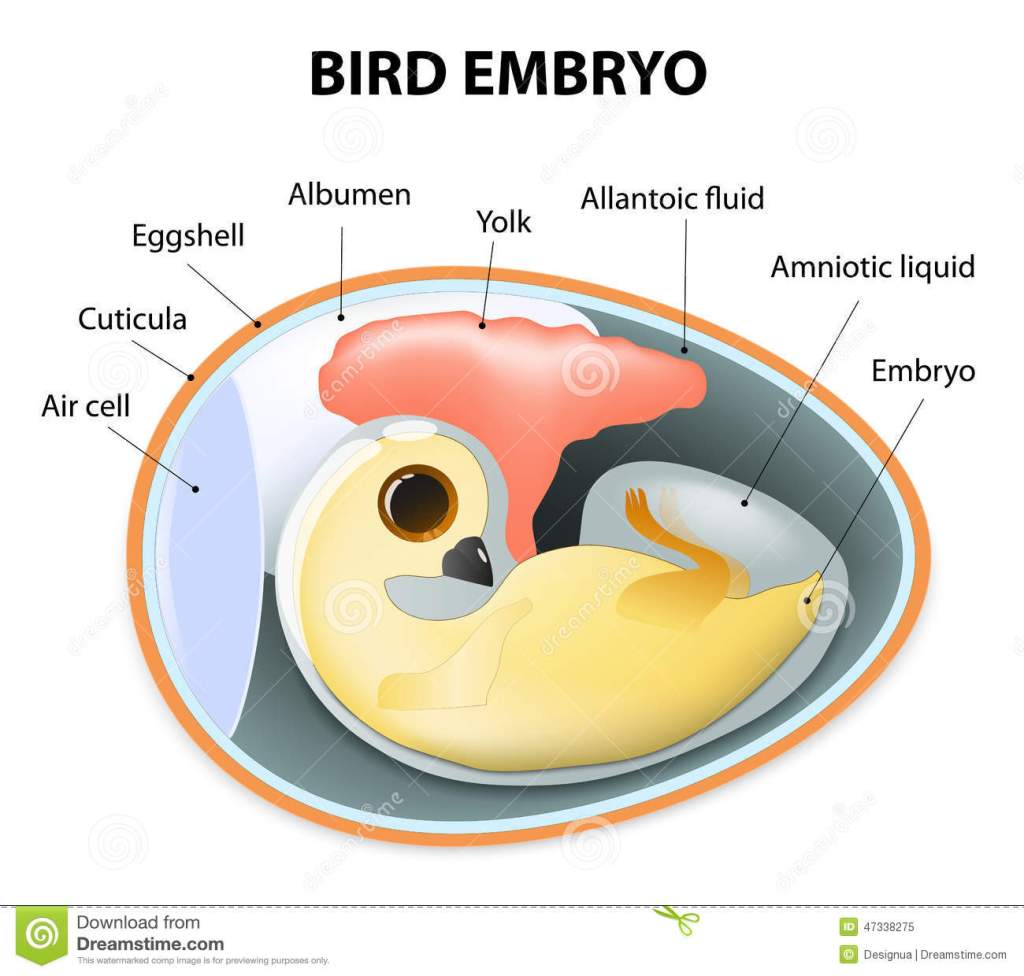

| The Dreaded Dead in Shell ………………… For those of you having a problem with dead-in-the-shell , lets have a look at the potential problems that can arise with each of these periods of incubation in more detail, so that hopefully the problem can be solved. Embryonic Death At The Start Of Incubation Deaths early in incubation can be detected by opening the egg and seeing that it is in fact fertile, but that the embryo is only poorly developed. The usual cause is poor incubation leading to the egg becoming cold after development has started. Possible causes include improper nesting material, over interference by the Fancier, mite or poor sitting by the hen ,bird room too hot or too cold or poorly ventilated, Also eggs are very vulnerable to vibration early in incubation. Shaking or jarring can kill the developing embryo either directly or by rupturing the yolk. This is of particular relevance when eggs are being transferred for fostering or Storage Embryos that are unlucky enough to have genetic abnormalities usually also die early in incubation. Genetic problems are more likely to occur with closely in-breeding of Fifes Deaths From Day 5 To Day 14 Of Incubation This is the longest period of the incubation process and yet it is the time when least deaths occur. The embryo is simply growing. The growing chick receives its nutrition from the yolk and deaths here can reflect nutritional problems in the hen. Hens that are correctly fed are more likely to produce nutritious yolks that support healthy embryos. The effect of breeding bird nutrition is very underrated. By simply feeding a blend of 2-3 seeds and a calcium supplement such as grit, it is not possible to prepare the hens for breeding. Fanciers who believe they can do this often accept as normal an elevated embryo death rate or several weak chicks in the nest. Although embryos can die of infection at any time during incubation, it is at this time of growth that they are most vulnerable. Certainly, there are some infections that can be carried by the hen that can infect the ovary such as Chlamydia and Salmonella. These can be incorporated into the egg at the time of its formation, and subsequently infect and kill the embryo as it grows. Infection can also pass through the oviduct wall into the egg. However, these types of infections, that enter the egg prior to laying, are in the minority. Most Infections that develop are caught in the nest after hatching. Nests that are dirty, poorly ventilated or excessively humid lead to egg- shell contamination and movement of infectious agents into the egg. Egg quality is also important. Cracked, thin, mis-sharpen or rough eggs allow easier entry of infection and are more subject to trauma. Poor eggs can be due to oviduct disease, but are more often associated with a nutritional deficiency: in particular calcium. Some fanciers will have noticed eggs with translucent clear lines running around the outside of the egg showing the eggs rotations, as it was passing down the oviduct. These thin areas can be an early sign of calcium deficiency. Embryonic Deaths At The End Of Incubation Through incubation a membrane called the chorioallantois develops around the chick. The chorioallantois acts a bit like a human placenta, in that it delivers air to the embryo after it diffuses through the shell. At the end of incubation the chick must swap from a chorioallantois respiration to breathing air. It does this in two stages. First it internally pips. This involves cutting a small hole into the air chamber at the end of the egg and starting to breath the air it contains. At this stage vibrations can be felt in the egg and chick will sometimes vocalize. After another 12-36 hours the second stage begins, with the chick cracking the shell and breathing external air. While this is happening the last of the yolk sac which is the chicks nutrition during incubation, is drawn into the navel. This eventually ends up as a tiny sac in the wall of the small intestine called Merkle’s diverticulum and lasts the whole life of the bird. Interestingly, during this time, the chick also drinks the clear fluid around it called the amniotic fluid. This amniotic fluid, and also the yolk sac contain the antibodies that protect the chick from infection in the first few weeks of life. While all this complex physiology is going on the chick is vulnerable to problems. Too high or low temperature or humidity during this time will adversely affect the chick. The usual problem is too high a temperature, or too low a humidity. This combination causes the shell and shell membrane to become hard and dry. This can lead to a healthy chick becoming exhausted. In addition to this, the chick quickly becomes dehydrated. I am sure many fanciers have helped these chicks hatch only to find them dead later. These chicks often die because they are dehydrated. Such chicks if given small drops of water will often suck them down greedily and survive. These dehydrated chicks are called “sticky chicks” because of the way they stick to the dry shell membranes. They are often found dead after hatching ¼ to 1/2 the way, emerging from the shell. If removed from the shell they often have unabsorbed yolk sacs and there is often dry, gluggy albumen still in the egg. In summary, hatchability can be improved by three simple steps:Improving nutrition in the months prior to breeding. A clean nest for every round, and ongoing nest box hygiene. Access to a bath around hatching |

EGG LAYING

If nutrition is adequate, the hen most often lays the eggs with no problems. Sometimes, particularly if not supplied with all the vitamins and minerals that they require, the hen will have trouble laying an egg.

Canary eggs hatch in 14 days. This is counted from the day that the hen starts to sit on the eggs, not from the day that the egg was laid. The canary chick hatches without any assistance from you or the parents. The little chick enters the world blind and naked, adorned by only a few wisps of down. The parents provide all care for the young.